Merge Queues with Bors

-- 1777 WordsRust, Developer Productivity, GitHub,

Many engineering teams and open source projects are introducing merge queues as part of their workflows. This post explores several reasons for using a merge queue and describes how to set up Bors, the merge queue implementation used by the Rust language project.

What is a Merge Queue?

A merge queue is an application that integrates with your version control system

(this post will focus on git and GitHub) to require that code changes are

merged atomically, which ensures that the main branch always contains a

version of the code that has been fully tested.

How it Works

Atomic merges are achieved by requiring that all pull requests (PRs) go through a queue in order to be merged to the main branch. This ensures that all branches are merged using a specific process. That process is:

- A PR is approved by humans, and the branch is added to the queue.

- Later, the branch is taken off the queue when it reaches the top. A canary branch is created by merging this branch with the main branch.

- The canary branch is run through the full test suite, ensuring that this exact version of the code passes.

- IFF the tests pass, the main branch is updated to point to the canary branch.

This process ensures that the main branch only ever points to versions of the code which have been fully tested. It may seem counterintuitive that this is not already ensured by a typical workflow, so let’s look at a concrete example of how this assumption can be broken.

GitHub supports several merge strategies when merging a pull request. In each case, when the PR is merged, changes are combined with the latest version of the main branch at the time of merge, which creates an entirely new commit. There are a number of ways in which this can result in untested combinations of code on the main branch.

The canonical example, paraphrased from Bors’ documentation, is that two pull requests are open at the same time (a common occurrence in popular projects):

- Invokes a method

foo()in a new location. - Renames

foo()tobar().

Both pull requests are branched from the same version of main, meaning that

the second pull request is not aware of the new call site for the function, and

does not rename it. The test suite for both pull requests will pass, and GitHub

will happily merge the two requests. The result is that main contains a broken

version of the code which invokes the nonexistent function foo() somewhere.

What about Branch Protection?

GitHub allows you to set a number of rules related to when and how PRs can be

merged. One solution to the above problem would be to “Require branches to be up

to date”. In the above example, the first PR would merge successfully, but then

the author of the second PR would need to rebase their branch on main (so

that it is up-to-date), and then would discover the problem when tests failed.

This approach works, but can become extremely tiresome for projects with many contributors and a long build process. Imagine now that there were three original PRs. After the first merges, the two other authors rebase and begin waiting for tests to complete. The first one to complete tests and merge wins the race, the other now has to rebase and test again. This results in multi-hour babysitting exercise to just land your one PR.

Production Artifact Builds

Many projects build a production artifact, such as container image with DryDock or a release binary, for each unique commit to certain branches. This artifact eventually makes it to production via continuous delivery, and can always be traced back to a specific revision of the main branch.

Unfortunately, as mentioned above, GitHub always creates a new commit when merging. This means that there is always some period of time where you have merged a change but the production artifact is still being built. It also results in a relatively unnecessary second build, since this version of the code should have been tested and built before merging. Lastly, there is a possibility that the final build could fail (even for spurious reasons), leaving you in a bad spot.

An astute reader would be familiar with git’s capability for fast-forward

merges, where a branch which is up-to-date with the main branch is merged by

simply updating the branch pointer for main to include the new commits. GitHub

sort-of supports this with their “Rebase Merge” option, but this still

creates a new commit (I think to add additional metadata), resulting in an

unnecessary build.

It is possible to manually conduct this merge on your local machine and then

push to main, but this is clearly not a scalable solution. Merge queues can

solve this problem because many of them support doing a true fast-forward merge

after the build on the canary branch has completed.

Too Many PRs

Even with the above process (rebase, test, merge) automated, there is one more problem. Say your test suite takes 30 minutes to complete, but your project averages 50 PRs a day. You will forever fall behind because you can only merge ~48 PRs a day when done one at a time! Many merge queues offer advanced functionality to support batching. This involves combining the changes from PRs that are approved at roughly the same time, testing them together, and then merging them in a group.

This can introduce some complexities: how to handle a failed group test (i.e. identify which PR introduced the failure), and how to prioritize or test specific PRs in isolation. Many merge queue implementations have functionality to handle these scenarios, but that is out of scope for this post.

Using Bors

Now that we have seen why you might want to use a merge queue, lets see how set your project up to use one. In this post we will look at Bors, which is the merge queue that you will see used on the Rust Language project repository.

Bors is a GitHub application, which makes it very easy to integrate with a GitHub project. There is a free hosted solution, but it only supports public repositories. If you want to use Bors with a private repository, you will need to host your own.

Hosted Solution

To use the hosted solution, simply install the GitHub App, making sure to share the repository you want to use.

Self-Hosted

The self-hosted option is relatively easy to set up and maintain as well. The Bors repository provides documentation for how to deploy Bors on Heroku which, at a high level involves:

-

Create a GitHub App for the deployment to use. The documentation includes detailed instructions for the permissions and events you should configure for your app.

-

Click below to create a deployment of Bors on Heroku. Fill out the application form with details from your GitHub App and click Deploy.

- Install the GitHub App you created in your account or organization and grant it access to your repository.

Setup

Once you have Bors connected to your repository, you will need to make a few final changes.

Test Triggers

Your continuous integration tool should be reconfigured to trigger tests for the

staging and trying branch, which are the branches Bors will use for testing

changes before merging.

I typically split up my tests into two sets based on how long they take to run.

Fast tests like linting can be run for all branches, so that you can see their

results prior to submitting to the merge queue. Slower tests are moved to only

run on staging and trying so that they are not run redundantly.

Bors provides some documentation for how to reconfigure a number of different CI tools.

Bors Configuration

The last step is to configure Bors’ behavior for your repository. This is done

by creating a bors.toml file in the repository root.

At a minimum, this file should specify the tests that need to pass on the canary branch before it can be merged. You can also specify the tests which must pass on PR branches before they are accepted into the queue. The literal name of the tests can be a little tricky to determine depending on which CI tool you use. Check out the documentation link above for some examples.

Workflow

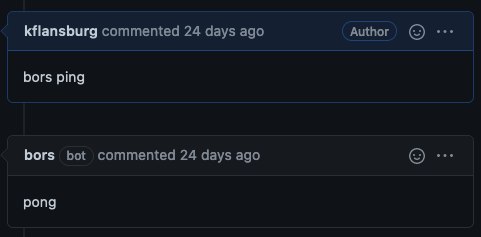

To verify that Bors is working, you can comment bors ping in a pull request,

and Bors should comment with a reply.

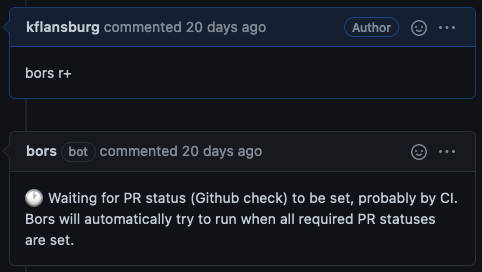

When you wish to merge a PR, instead of pressing the big green merge button,

comment bors r+. Bors will comment in acknowledgement. If you configured Bors

to require some tests to pass before adding a PR to the queue, and those tests

are still running, then Bors will comment to let you know that it is waiting for

these to complete.

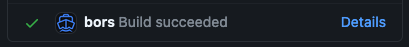

Once the canary tests are running for the PR, you should see a new GitHub status from Bors on the pull request. This status will show a green check once the tests succeed.

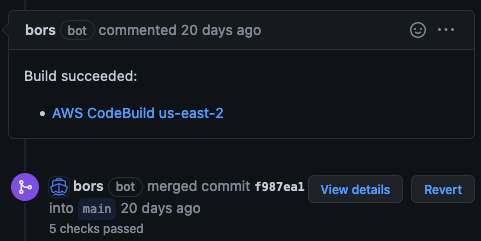

When the tests pass, Bors will automatically merge the changes, and comment a summary of the tests run on the canary branch.

The merge commit will include a summary of the PRs included in the merge (if using batching), and indicate all PR authors as co-authors of the commit.

To learn about all of the possible commands for Bors, check out this documentation.

Troubleshooting

If you are using the hosted offering, be sure that the repository is not private. This is unsupported.

For the self-hosted offering, if Bors does not seem to be responding to comments

or successful tests, double check the events that the GitHub App is subscribed

to. The necessary events are indicated in the

list of permissions

in Bors’ documentation. You may also wish to double check the names of the tests

you specified in bors.toml. You can view the log output from Bors on Heroku,

as well as the GitHub webhook payloads (in the App configuration, under the

Advanced tab) to cross reference the names of the tests being reported.

Conclusion

Merge queues are a powerful tool for automating your code contribution process. They can be especially impactful for projects that have long-running test suites and many active contributors. Bors is one implementation of a merge queue which can be set up very easily for public projects. Private projects can set up a self-hosted deployment of Bors quickly using Heroku as well. Thanks for reading!